27 Apr Exploring the food commons through craft

Each member of the Crafting the Commons network has been invited to write a post for the blog, capturing their thinking about commons and commoning as the project unfolds. This post is by Rachael Colley.

Rachael Colley is an award-winning interdisciplinary artist and senior lecturer in Jewellery and Metalwork at Sheffield Hallam University. Her current research brings together jewellery, created predominantly using food waste, and ambiguous artefacts for eating. She invites diners to wear these visceral jewellery pieces whilst consuming food with alternative dining tools.

Food is a powerful, far-reaching form of commons. Like craft, its unique unspoken language both reinforces and transcends class boundaries and enables more fluid cross-cultural communication. As materials, food-stuffs, and more specifically food waste, awaken the senses, with the more visceral of these dining remains tending to initiate instinctive ‘gut’ reactions from those experiencing them. As historic finds such as the 110,000-year-old shell beads of Nassarius kraussianus from Blombos Cave evidence, some of the earliest forms of jewellery discovered suggest the re-purposing of food waste, placing these organic materials onto as well as into the body. Ingold states that,

“In the art of enquiry, the conduct of thought goes along with, and continually answers to, the fluxes and flows of the materials with which we work. These materials think in us, as we think through them.” (2013, p.6)

He intimates the fluid physical nature of the making process, something I keenly explore in my work, which is designed to act as a form of ’cause jewellery’, drawing attention to the issues surrounding food waste in a more personal and intimate way by creating art jewellery crafted from discarded organic consumables.

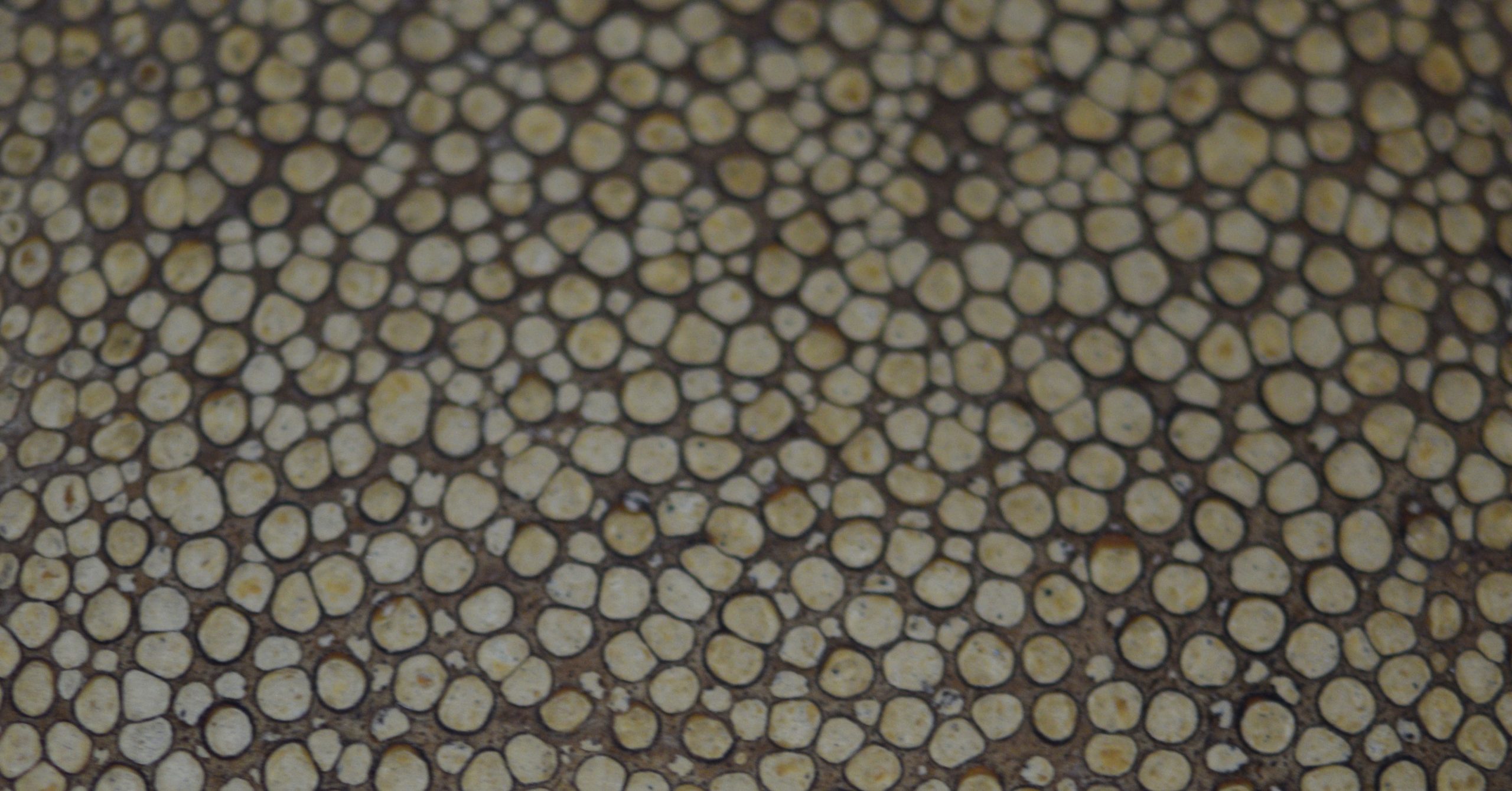

Sha-green series transforms waste citrus fruit peel into a series of sustainable, biodegradable, vegan wearables that present a material alternative to the traditionally animal-based luxury decorative surface shagreen (ray or shark skin). This scented material comes alive when worn; as it is warmed by the body it emits a subtle fruity fragrance. The jewellery’s limited lifespan highlights the fleeting nature of human existence, suggesting the ultimate end that conventional jewellery circumvents through its endurance.

I would consider one of the initial stages of my creative process, the gathering of food waste, to be a modern-day form of gleaning. Gleaning was historically the gathering of the leftover harvest, predominantly by the poor, to feed them and their families. Gathering and categorising the materials I collect is one of my favourite stages in my design process. Some people would probably call me a hoarder, but this practice provides a very important pool of inspiration for me. In researching gleaning further I was struck by a practice I felt could be considered common to craft-based and artistic practices.

I look a lot; I touch, smell and taste what I can.

I look down at the floor a lot.

I often find it hard to walk past things that interest me without pausing to take a closer look.

I want to capture, save and collect them, whether that’s physically or through some other means like photography, film or drawing.

Sometimes, if I can, I stop and stoop to pick them up.

Agnés Varda’s film Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I, 2000) beautifully explores how gleaning has evolved as a more modern day practice, with some gleaners easily able to gather vast quantities of dumped potatoes, mostly because they are the incorrect size or shape, and do not meet the standards set out by the sellers. Wasted food across the world is a serious issue that has been gaining attention over recent years, especially in reference to our current climate crisis. Organisations, such as Feedback, support work around food commons and have established initiatives that include their gleaning network, to help tackle the issues surrounding wasted food stuffs from a range of perspectives. Vivero-Pol et al state that,

“capitalist thinking and its practices have increasingly transformed food – an essential element of life – into a private, mono-dimensional commodity for mass consumption in a globalized market. Over the last decade, however, there has been an increased recognition that this view of food as a commodity, as a social construct, can be challenged. Food can be re-conceptualised differently: it can be valued and governed as a commons, and it is constructed as such in a range of initiatives in all world regions.” (2019, p.3)

Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (McDonough and Braungart, 2002) encouraged me to more consciously approach my design start-point by first considering the product’s end-point, essentially its ‘death’ and re-entry into a specifically designed lifecycle. Circular Design presents the idea of a closed-loop economy where materials, nutrients, data, etc, are continuously repurposed and fed back into the system. This alteration, or circular re-ordering, of a more traditionally linear design methodology helps to shift the focus and perspective of the designer to holistically approach the formation of a lifecycle and ecology for the proposed product. This is a system that designers and makers should all consider and work towards, as it’s clear that the current ‘take-make-dispose’ economy will not support us in the long-term. Open access online resources, such as those provided by Materiom, are a great example of commons thinking combined with circular design principles. Materiom collate and publish a wide range of recipes and data on materials made from abundant natural ingredients, including many food waste components.

For We Are Commoners I intend to work collaboratively with my local council and land management personnel to make use of organic waste gathered from common land. I will combine these materials with food waste to create biodegradable materials that are designed to re-enter the habitat they’ve been removed from at a later date, working within circular design principles whilst also commenting on the current model’s ‘defined user period’. These provocations for the objects end-of-life acts correlate the carefully crafted art jewellery artefacts with the model followed by the costume jewellery of fast fashion in marking their useful end, and in encouraging the formation of new rituals that acknowledge the value of craftsmanship. The proposed acts may resonate with ancient ritual practices and are designed to celebrate the nourishment that is provided in many ways by both the land and craft, connecting with the nostalgia felt for craft and the idyllic commons of historic myth and legend.

“The idea of the commons offers a romance, and through this romance, a way forward, a way to think out of the despondent political narratives of ecological destruction, polarisation and dispossession, and a counter-narrative to that of the inevitable and uncontrollable force of neoliberalism. Above all else, it offers a glimmer of possibility that change can occur incrementally, and that small acts matter.” (Dawney, Kirwan and Brigstocke, 2015, p.3)

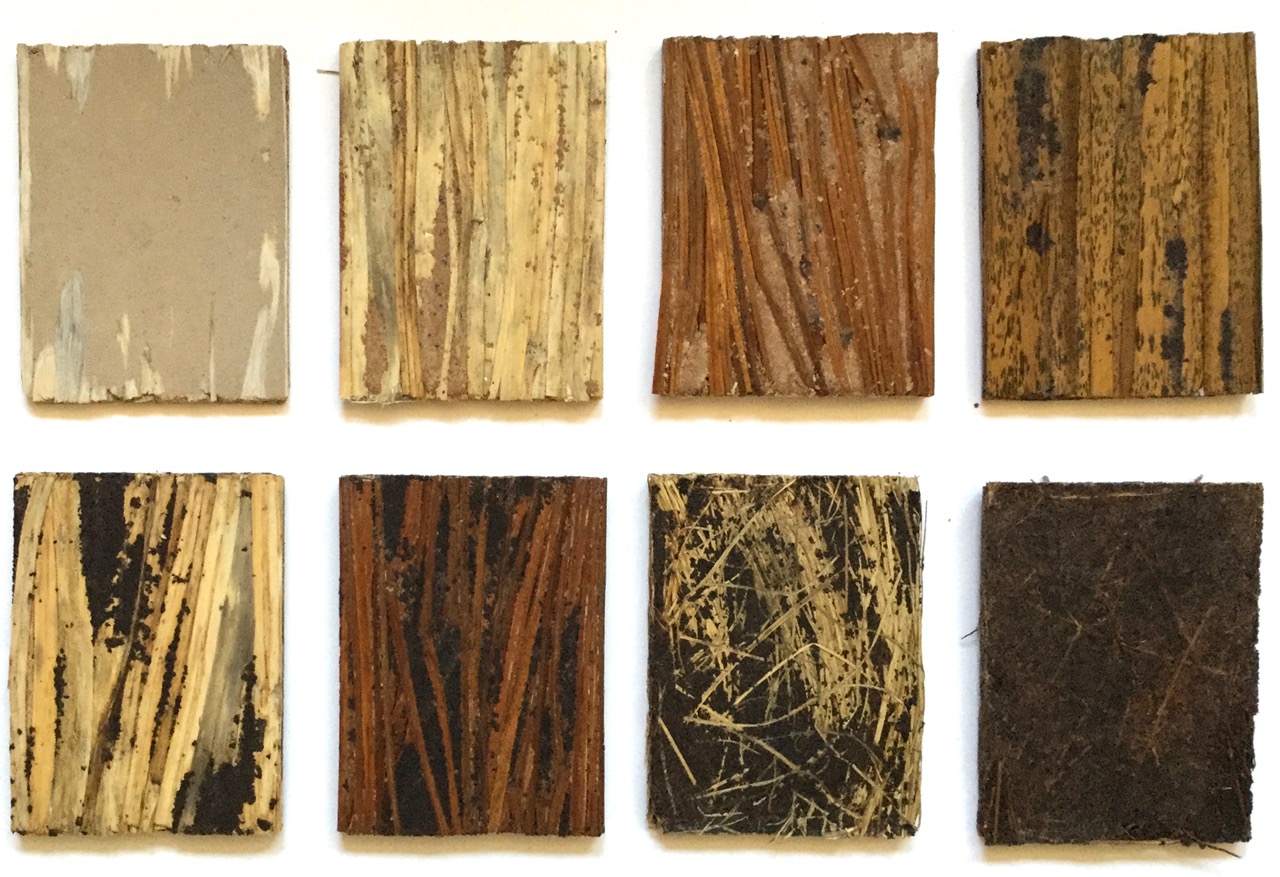

Based on some initial material tests, bracken stands out (top right material test) as an abundantly available material with significant potential to reference or mimic the qualities found in some luxury high-end exotic woods, especially those used in veneers for marquetry and other decorative woodworking details. Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) is a native British fern commonly found in woodland and heathland (Royal Horticultural Society, 2020). There are copious swathes of bracken across many areas of common land and it is considered undesirable as a garden plant, as it can take over. It is also considered undesirable due to its toxicity, as its spores contain carcinogens that are dangerous if eaten by humans or livestock. Eating the young fronds is still considered a delicacy in Japan, but their ingestion can be linked to an increased likelihood of oesophageal and stomach cancer. Bracken is increasingly used in the creation of peat-alternative composts; however, the gathering of bracken for this purpose in late summer is not advised, as this is when the spores are released. For this project I have been gathering bracken stalks from February to March, helping to clear some areas and also making way for new growth to come through.

References

CAPITAL CRISPIN [Online]. Available: https://www.capitalcrispin.com/ [Accessed 10 April 2020]

DAWNEY, L, KIRWAN, S, BRIGSTOCKE, J. 2015. Space, Power and the Commons: The struggle for alternative futures. London: Routledge

FEEDBACK [Online]. Available: https://feedbackglobal.org/ [Accessed 10 April 2020]

INGOLD, T. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Oxon: Routledge

MATERIOM [Online]. Available: https://materiom.org/ [Accessed 10 April 2020]

McDONOUGH, W, BRAUNGART, M. 2002. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press

ROYAL HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY [Online]. Available: https://www.rhs.org.uk/advice/profile?pid=445 [Accessed 10 April 2020]

VARDA, A. 2000. Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I). Cine-Tamaris production

VIVERO-POL, J, L. FERRANDO, T. DE SCHUTTER, O. MATTEI, U. 2019. Routledge Handbook of Food as a Commons. London and New York: Routledge