11 Feb Preserving or policing commons?

This blog post, by Dr Naomi Millner (University of Bristol), is based on material presented at the Crafting the Commons workshop in Nottingham (December 2019). Parts of the post have also been published in an article written for the STIR Magazine special issue on Commons published in Spring 2015.

In this post I reflect on what we can learn about “commoning” from an historical struggle to protect and preserve commons in the UK. Specifically I will refer to the creation of a Commons Preservation Society in the 1860s in response to the perceived threat to expanses of “wastelands” and open spaces on the edge of expanding towns. I use the verb, commoning, here in contrast to commons, noun, to emphasise what I hope the art and crafting experiments associated with this project can reach towards. When commons are often being romanticised, as something lost that might be recovered, there is a tendency to associate them a moral imperative to return to the past, and to leave the structures of power that animated past societies relatively unquestioned. Commoning, on the other hand, refers to the process of making things in common, which is always precarious, provisional, and context-specific. Commoning is a kind of labour that involves connecting, experimenting, claiming things, improvising, learning, and finding new kinds of affinity. It is always being reinvented afresh.

The Commons Preservation Society

The Commons Preservation Society (CPS) is considered to be the oldest of the UK national ‘amenity’ bodies – voluntary organisations set up for the purpose of preserving the art and architecture of the past. It was founded in the 1860s as an organised pressure group with the ambition of protecting the parklands and heaths that were at risk of a new wave of enclosure associated with rapid urbanisation. The group were hugely successful, campaigning effectively for the preservation of significant portions of the English countryside. Called “commons,” these newly-protected sites – including Hampstead Heath and Epping Forest – became emblematic of a wider movement to recognise open spaces as a critical part of national heritage. Situating the Society in terms of longer trajectories of radical politics is complicated, however: on the one hand, the new CPS – which included politicians, lawyers and historians — played a vital role in translating the imperative to protect common resources into legal mechanisms and claims. On the other, their activities were grounded in a romantic vision of nature that went on to support bourgeois leisure ideals, and to strengthen calls for new kinds of spatial policing.

The CPS were certainly not the first to organise in the name of the English commons. The Chartist movement, which had been active between the 1830s and 1850s, had mobilised the term commons in its occupation of public spaces such as London’s Hyde Park, calling for rights for free assembly and rejecting the policing of public space. This gave rise to new concepts of “public space” which would become central to democratic political thought, even after the Chartist movement faded out. Before this time, hedge-breaking, Leveller and Digger movements had also claimed ‘commons’ when the Manorial system of land management, dominant since Domesday, were being legally dismantled throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries – the first main wave of enclosure. This process of enclosure continued into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, although in the time of the CPS social movements were no longer responding primarily to the conversion of agrarian land into private property. Instead the principle concern was the open land on the fringes of Manor estates, the former “wastes” or “commons,” which were being sold off for large urban building projects.

The tensions surrounding the commons and its relation to liberty were felt especially in London. In 1864 when a bill was proposed for the enclosure of Wimbledon Common, Frederick Doulton, the MP for Lambeth, was able to instigate a House of Commons select committee to interrogate the bill and to re-examine the state of open spaces in London. This committee produced a report in 1865 on London’s commons calling for an immediate end to enclosure; the recognition of the rights of the ‘public’ over the commons; and the imposition of regulations for their better management. The CPS was founded the same year with the purpose of giving effect to the select committee’s recommendations.

Policing or preserving commons?

George Shaw-Lefevre, the first Baron Eversley, was a key figure in the new Society, and it was in his chambers in the Inner Temple on July 19th 1865 that the Society was inaugurated. Eversley had become a prominent member of a radical group of Liberal MPs intent on reshaping the party for social reform. Leading up to the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, Parliament had been dominated by debates between well-represented land-owners on the one hand, struggling to keep existing limitations on corn imports to ensure the premium value of their crops, and new industrialists on the other, keen to open up the markets and force down the cost of labour. Eversley and his allies, including J.S Mill, Lord Mount Temple, and Professor Huxley developed a “third-way” argument within this debate, premised in ideas of protecting a public good. This was a relatively new idea at the time. It called for the creation of collective forms of ownership, through which land and cultural heritage could be protected from excessive development – later leading to creation of institutions like National Heritage and the National Trust. However, while opposing the pursuit of individual gain, this public good was not really a rejection of the basic principles of private property ownership at all. The “commons” here was understood as national heritage and a poetic source of inspiration, animated by romantic poetry and artwork, such as paintings by Constable, poetry of Keats and Wordsworth. Unlike some of the earlier movements, the commons is also connected here with ideas of “improving” the poor by giving them access to green spaces.

The adoption by Parliament of Eversley’s report did, however, lead to the passing of the Metropolitan Commons Act of 1866, which made enclosure of the London commons practically impossible. It also made Lords of Manors quickly rush ahead to enclose, beginning with Hampstead Heath. It was at this moment that the first solicitor for the CPS, P hilip Lawrence, began to collect evidence of the continued existence of common rights on the Heath, since “time immemorial”. The battle for Hampstead Heath was concluded successfully in 1868, and was followed by protracted campaigns for commons, and later forests, including Wimbledon (1865-70), Wandsworth (1870-71), Plumstead (1866-71), (1868-71), Epping Forest (1865-71), and Berkhamsted (1866-70).

This sequence of campaigns reflected the emergence of the CPS as a growing and increasingly formidable force of influence. When a park or heath was threatened, the central working-group would bring a planned enclosure to local public attention, raise the issue in national papers and work with local associations or individuals to build interest for a local CPS group. Then, the society’s historians and lawyers would gather evidence of the continual practice of commoners’ rights on the site in question through history, and into the present day. A local resident with sufficient influence and funds – often a personal friend of Eversley – would then be prevailed upon to bring a legal challenge against the Lord of the Manor, while public events were organised to rally the newly christened “commoners”.

In the way it connected influential people to achieve its goals the CPS was characterised by both conservative and radical progressive tendencies. The Society’s appeals were based in ideas of historical heritage and nostalgic visions of the pre-industrial English countryside and their activities were largely dominated by the interventions of already powerful white men. On the other hand, its models for action were inspired by experiments in democracy abroad, and by progressive economic critiques – for example, from social thinkers such as John Ruskin and William Morris.

This tension is one reason that it is very difficult to describe the CPS in terms of its class relationships. Some have portrayed the CPS as a moralising force of the bourgeoisie, acting to ‘improve’ the working class, police new park spaces from ‘rough’ or ‘unseemly’ uses, and ensure the access to recreational spaces for the middle classes. Yet again, others claim this reading downplays the radical reading of common and customary rights that drove the activities of the CPS – for example, a dramatic fence-breaking action on Berkhamstead Common in 1866 – and their role in stimulating popular dissent. In this sense it is also important to note the role of the CPS in facilitating new coalitions between groups, and in many ways acting the catalyst for the birth of new prototypes of early twentieth century labour politics.

Commoning today

Today, notions of commons take on new currency as forms of enclosure associated with corporate land-grabbing and neoliberal privatisation exert increasing pressure on the possibilities for rural and collective life. These commons are not the same as the commons claimed by the CPS, which in turn are not the same as the commons claimed by the rural struggles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries or the Diggers.

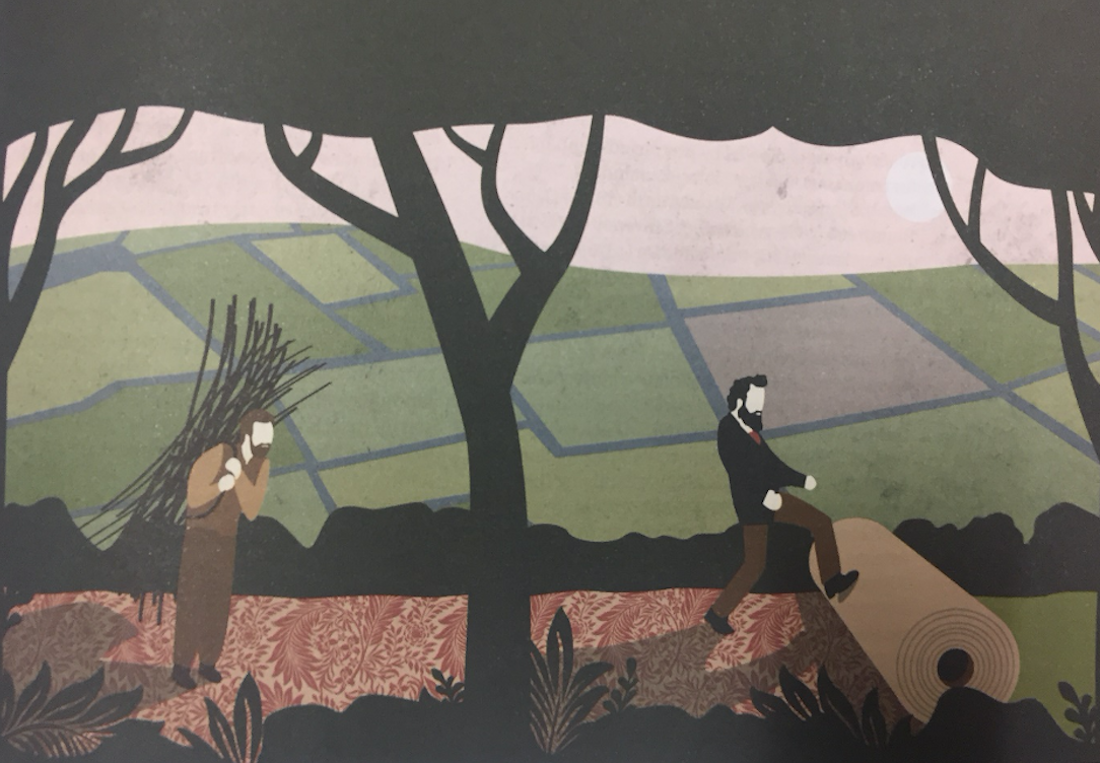

However, I want to suggest by focusing on the verb – commoning – we can think about what these movements hold in common. The means, for example, through which associations were built between groups who previously had little in common, in order to claim something. We can think about the shared activities – a meeting in a school hall, a shared lunch, a walk to survey the grounds, the performative recreation of ancient rituals to show that commons had been used for time immemorial, and the fresh sense of shared goals that must have accompanied each campaign. Different constituents would have been animated by different visions of the commons – art and poetry, the feeling of the wind on a daily walk across the common, the need to gather firewood, a sense of belonging or freedom. However, they were united in particular moments when they gathered to claim something, and to intervene on the legal mechanisms through which land could be bought, sold and managed.

To conclude, we can continue to be inspired by innovative forms of social organising that have intervened into the law and acted against processes of enclosure that continue to divide social worlds and privatise land. Movements like the CPS give us images and animating energy to continue inventing our own agendas and means. However, paying attention to the long histories and complex geographies of claiming commons asks us to remember that more than one vision of common life is always at stake.