04 Feb A technophilic allegory For Commons Stories

At the first full network meeting on 11-12 December, five academics shared diverse stories about the commons. This is the text of the story shared by Dr Jeremy Kidwell (University of Birmingham). The story is also posted on Jeremy’s website, with a Creative Commons license.

In 1964 two psychologists at the University of Birmingham, Profs. Smith and Farrier, made an astonishing discovery. They were conducting fieldwork on a remote island off the coast of the Australian Territory of Papua (now known as Papua New Guinea) as part of a groundbreaking research project in what was then called psychophysics. The project had been designed to test for the cross-cultural saliency of certain forms of aliamentary stimuli. However, when they disembarked from the repurposed oil tanker which served as their research station and arrived on the island, they realised that in contrast to what their reconaissance had suggested, the island was wholly unpopulated. In the midst of great consternation and foraging in an attempt to discover the reason for this strange and seemingly impossible migration of people they stumbled upon something which had been hinted at by their colleagues in physics, but which had never gotten beyond the realm of pure speculation: a temporal-dimensional rift. Gazing upon the shimmering side of a boulder the size of ten men, which surely should not be shimmering, they observed the dim outlines of an unfamiliar landscape, which then appeared to move. Being men of science, and naturally inquisitive as psychologists often are, Prof. Smith attempted to ascertain the nature of this artwork and was astonished to find that the rock was not merely overlaid with some clever Papuan artworks, but was in fact a portal to an alternative dimension. After some weeks of collecting data on this anomaly, they concluded that the portal was relatively stable gateway to other worlds, and surmised that it could be entered safely by a human person who would appear in that other world. Being naturally generous men, as psychologists often are, the two professors returned to their marine research vessel and began radio tranmissions in an attempt to correspond with key colleagues in the British Psychological Society. 1964 was generally an optimistic year, full of hope and excitement for what lay ahead in the modern world. Yet, as these two professors knew, the task ahead of building a better society was laden with challenges. They realised this was a once in a lifetime opportunity to fashion a new and hand-selected population for a utopian society.

Two months later, they returned with their research vessel brimming with 100 of the brightest minds they could reasonably persuade to join them in this undertaking. Profs. Smith and Farrier had discovered that the portal was only stable for a limited window, so they knew that this was likely to be a one way journey. So, one by one, 50 men and 50 women and a cocker spaniel (for obvious reasons) passed through the portal with a small complement of scientific equipement, biological specimens, and other reasonable provisions for this undertaking. For reasons which they were unable to ascertain, the entirety of their scientific equipment was completely useless. And their biological speciments found some aspect of this new landscape to be entirely unwelcome and promptly died. Yet this group was able to carefully eke out a survival on what had turned out to be an astonishingly beautiful and exciting landscape.

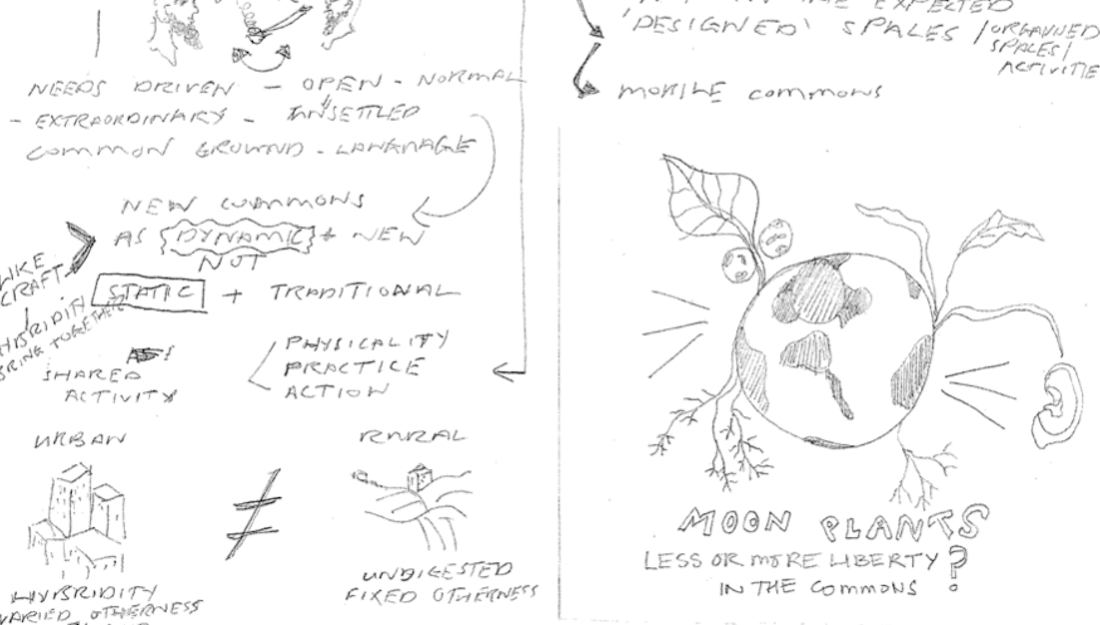

About two weeks after their arrival, another member of their party, Prof. White – a female botanist, was walking along collecting samples and munching on a local fruit from what the group had begun to call a moonplant. She discovered something astonishing in a rather unscientific way: she tripped over a buried stone and cursed loudly mid-bite into the stem of her fruit. Much to her surprise, her curse was repeated verbatim back to her just a moment later. Apparently, this was no ordinary fruit. Subsequent investigations revealed a variety of remarkable abilities which this semi-sentient and unusually cooperative plant was capable of. If one were to speak for any length of time into this fibrous fruiting plant, it recorded every word verbatim and through somatic memory and special vibrations, the stem could somehow recall and repeat them back. Amateur musicians realised that it could also record their singing with high fidelity and play it back at any particular time with a special kind of shake. But the most significant discovery came about when Prof. White was experimenting with multiple plants to see whether there were variations in their abilities. If one were to bring two of tubular flowers of the moonplant into direct contact they subsequently developed the ability to transmit recorded sound across great distance. One a remote planet at an uncertain cosmic time, this “resonance” as it came to be called, was an extremely exciting discovery for this group of scientists. Over the next decade time they developed a complex system of what we would now call data storage and transmission. And as the years elapsed, they began to gather more significant quantities of data about the island, alternative technologies which functioned there and stories, poems, and songs about their new life. This humble flowering plant became incredibly precious. Once rendered biotically resonant, any moonplant could recall data from another moonplant and could transmit new messages, not just to a single other node, but to any number of plants. A group of first-generation planetary teenagers developed a radio station. Some sciensts began the task of recording audio reports of their discoveries and syntheses of their attempts at engineering in this new space for posterity.

As seems often to be the case with utopian societies, after about 20 years of life together, differences of opinion developed into more substantial rifts. Some groups broke off and relocated to other more remote islands. Others remained together but their relationships became rancorous. Because the moonplants were their primary mode of communication, they were soon caught up in these bits of relational friction.

One splinter community made the decision to centralise control of moonplants. A rotating delegate would hold possession of all resonant moonplants and that person would pass along outgoing messages to other planetary collectives, recall information upon request, and provide digests of incoming communication for the sake of convenience for this otherwise very busy community. To operate a battery of moonplants was complex enough that the were reasons not to rotate very often. In this community, this rotating moderatorship became the seat of incredible power, often contested.

Another, more anarchistic community decided that every person should have their own moonplant, and thus made the surprising decision that all moonplants were to be strictly rationed and artificial scarcity would be enforced for these otherwise ubiquitous plants by destroying all new moonplants except for those which were needed for newly born human individuals as they came into their age of majority, which was set at the age of 11.

On the mainland, things remained undetermined for a time. Some individuals held a variety of differently resonant and interconnected moonplants. Others formed cooperatives to sustain carefully curated moonplant resonance networks.

By this time there were also lone individuals living as hermits in various outposts. Hermits proved to be a source of inspiration and good humour, but also proved the source of some unfortunate mischief in several crucial ways. Many of these hermits had particularly resonant moonplants and thus maintained some level of connection with multiple others. It was eventually discovered that one of these hermits was deliberately destroying early and important moonplant recordings whenever they were found to feature male voices or the barking of dogs. This ability to destroy data held in the network was previously unknown, so the mainland group was astonished to discover that several key historical narratives were suddenly and irrevocably missing. Another hermit, with a rather unfortunately strong sense of their own ideological ability discovered that by using a particular vibration they could trigger other resonant moonplants to convey messages involuntarily. What ensued was a disappointing and paradoxical turn: at any given time, moonplants might be spouting off obscenities, losing information, and in one case playing a single song unceasingly. One or two individuals among the anarchist colony destroyed their moonplants, preferring to avoid this unwelcome interchange. They were forced to rely on others as a proxy still in possession of a living moonplant to access information which might have importance to them.

At their third decennary celebration, a significant contingent of colonists and their progeny gathered, purportedly to celebrate their persistence and the beauty of their common life, yet a pallour hung over this convocation. The moonplants upon which they had become so dependent for daily life and scholarly achievement, had become problematic, confusing, even dangerous. A small group discovered a new temporal-dimensional rift had opened on the eastern shore and was covertly planning a second migration with moonplants in hand. How might they organise their new life with these sentient plants so as to avoid the problems which arose in their common activity? For the discussion that follows, I will invite you to “choose your own adventure” and set a plan for this new generation…

Key questions: How do we manage authority, disagreement, rules, and distribution of power once commons are established?