10 Dec We were commoning when …

Alinah Azadeh is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, maker and cultural activist of British-Iranian heritage. She has used installation, textile, writing and live interaction to create poetic and provocative narratives around identity, loss, and our personal and social relationships, working with museums, galleries and across diverse communities in the UK and internationally for over 20 years. She is currently inaugural writer-in-residence for the South Downs National Park, out at the Seven Sisters Country Park and Sussex Heritage Coast until the end of 2022 and lead writer/ curator on We See You Now, a related literature and landscape programme funded by Arts Council England.

Alinah’s work for We Are Commoners, commissioned as a residency by Craftspace and Midlands Arts Centre, resulted in Craft in Common, an online video resource exploring emotional/affective commons through hands-on, guided making across the five themes she felt were most relevant to the emotional labour needed for these pandemic times: Courage, Care, Loss, Connection, Repair. The Courage Medals resource in particular has since been used to facilitate live workshops and the making of hundreds of medals across marginalised communities in the UK.

Imagination is one of the spoils of colonization, which in many ways is claiming who gets to imagine the future for a given geography. Losing our imagination is a symptom of trauma. Reclaiming the right to dream the future, strengthening the muscle to imagine together as black people, is a revolutionary decolonising activity.

Emergent Strategy – Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, Adrienne Maree Brown (p18), AK Press

Rural belonging is often predicated on people’s sense of a historical relationship to the land. It is precisely this sort of historical sensibility that enables white Britons to more easily ‘inhabit’ the countryside when they visit it, or dwell in it. Huggan and Tiffin argue that a sense of white, rural belonging is expressed as a form of ‘patrician privilege’ which exceeds more residential rights and amounts to ‘emotional possession’. This feeling of ownership is, they suggest, ‘vouchsafed by romantic appeals to English cultural heritage’

Green Unpleasant Land: Creative responses to Rural England’s Colonial Connections, Corinne Fowler (pp52), Peepal Tree Press

Crafting and writing through crises

Through the winter of 2019 and into spring of 2020, alongside developing the Craft in Commons video resource and keeping family, mind and body together as the first Covid lockdown hit, I was also doing a lot of writing. I had an Arts Council England research and development grant to progress my first book and also to develop a landscape and literature-based pilot project. I produced a new piece of speculative fiction writing. We See You Now (prologue), set out along the cliffs of the Seven Sisters and along the Sussex Heritage coast. It centres around an encounter, set in 2053 (when sea levels have dramatically altered the landscape) between a girl from across the water and the cliff itself, inviting the listener to reflect on their relationship to land, climate, migration and future.

This story, the first of a whole series since commissioned by the South Downs National Park Authority and co-funded by Arts Council England, led to my current post as writer-in-residence and a two-year programme of work which will unfold as podcasts, writing/audio commissions, live events, retreats, workshops and an anthology.

The project explores and highlights aspects of overlooked human-made & colonial heritage across the area in order to expand historical awareness, through my own writing and the work of a cohort of writers of colour who have been involved in walking and writing retreats that I have run, inspired by this particular landscape (produced by Sussex-based diverse arts and heritage organisation Writing our Legacy). We See You Now is rooted in an embodied and decolonial approach to natural heritage itself; seeing and writing ourselves as an intrinsic part of nature, in a constant state of change, whilst the metaphors of the rapidly disappearing chalk coast and its status as border also provide an opportunity to use our lived experiences of loss, renewal and resilience to show creative solidarity with those being most affected by climate and life changes through migration, both locally and globally. It has multiple partners across cultural, heritage and community sectors.

The project also intends to disrupt the unspoken idea that the ‘right’ to a free relationship to our nature-based commons such as land, sea and air is tethered to a historical relationship held by a certain kind of citizen with a particular migration/legal status, and this means writing in ‘invisiblised’ stories and giving platforms or tools to allow this to happen.

Less bucolic rural idyll, more global imaginary

With my prologue story, as with my very first courage medal, I intended for it be both a listening experience in itself and to be used as an example/prompt/spark for others to use to write their own work, preferably whilst outdoors or near water. I tried this out during the first 2020 pilot walking/writing retreat, which, because of lockdown, happened between zoom and the participant’s own closest outdoor landscape they could access. Some were shielding so they used the views through windows, video sent from us on whatsapp from outdoors, or the story I wrote as an imaginary landscape. I developed writing prompts for these writers to examine how their relationship to coastal landscape, loss and change had been shaped by the legacies of their own family migration – and for us to collectively explore and write in an embodied way, considering our relationship to the more-than-human (or ‘nature’) and the impact of rapid climate change on this and other island nations as we move into an uncertain future.

Much of the land around us in the south east (including Lewes, where I live) is classified as part of the South Downs National Park, but a great deal of it is actually privately owned through estates which operate an old feudal model (of lords and tenants..) and some is also National Trust or Council-owned land. This is reflective of the fact that 92% of land in England is privately owned, and I am aware that this legacy /reclaiming of the loss of nature commons / common land after Enclosure (related in part to how the spoils of offshore slavery wealth were spent) is something that runs through much of the thinking and creative inteventions within this Crafting the Commons network.

The Seven Sisters Country Park, as of last October, is the very first piece of land that the South Downs National Park are direct landowners of and brings it a step closer in terms of the public’s relationship, to something more like common land…or at least to expanding the ‘use rights’ that this land can be imbued with, for public use and for nature-based solutions to mitigating the effects of the climate emergency, without having to consult or persuade private landowners or farmers to get on board. It is also one of the reasons why I was commissioned, to consider and creatively respond to what an equitable ‘landscape for all’ might look like. Using creative writing to unearth overlooked heritage, creating visibility and a space for those of us from first, second and third generation migrated heritage within the narratives of an iconic landscape that is both a well-loved area as well as a hardening border – is a core part of this.

During the Crafting Worlds in Common symposium, Keynote speaker Prof. Peter Linebaugh spoke about Gerard Winstanley, the 17th century English religious reformer, political philosopher and activist who founded the Diggers / True Levellers. Their land-based activism – in the face of the Acts of Enclosure (begun in 1604) – casts a direct historical line forward to the 1932 Mass trespass of Kinder Scout, the movement apon which the foundations of the modern National Park’s creation are based. The echoes of reclaiming access to nature are present now in current local activist campaigns within the South Downs, such as the Landscapes of Freedom campaign, which seeks a limited Right to Roam across England through an extension of the Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act (2000). It seems to be resonating particularly with those in the urban and peri-rural fringes of Brighton and Hove who are using poetry, music and art in the landscape to highlight this cause.

During the symposium, Dr Leila Dawney also spoke of commoning in relation to land – and how the image of the rural within so many commoning activities is ‘an often-romanticised bucolic English idyll…’ and that what is needed is ‘more global imaginary …’ and also of the ‘Importance of creating trans-global connections’. I then realised that the ideas around sharing freely the different ways of making objects I used, to find ways of coping and creatively responding to the current crisis, for Craft in Common – and my involvement with this craft-based network, was clearly influencing the development of my writing-based We See You Now project. And I wanted to share examples of this in practice over the last year.

Commoning as restorative, creative resistance

As the rage and solidarity of Black Lives Matter shook us all up as human beings and creatives (especially those in our groups who had been deeply involved in street protests) and made our connections over further zoom Writing retreats and monthly ‘writer check-ins’ even more potent, the act of bringing these fellow writers into closer and collective relationship with the Seven Sisters landscape began to feel like a proposed act of restorative care, as much as creative endeavour and resistance. With full support now from the South Downs National Park Authority for my residency and an Arts Council project grant for the programme, in September 2021, the first in-person Walking and Writing retreat brought a cohort of us together to explore write, bond and dream together around the chalk coast and the meanders of Cuckmere Haven.

So, how was this commoning?

We were commoning as we sat down in a circle at the start of our retreat in the village hall at East Dean, within reach of the sea, to speak about the barriers we have experienced in freely exploring the rural landscapes on our doorsteps, the wounds that needed healing; whether from rural racism, or a lack sense of safety / discomfort when out solo in the landscape due to gender, class as well as race. This speaking brought a recognition and sense of relief of not being alone in these feelings and experiences.

(Note: there are certain ‘beauty spots’ across this landscape such as at Birling Gap & Cuckmere Haven, now frequented by huge numbers of very diverse visitors from London and global tourism thanks to the pandemic and efforts by the National Trust and the Park to be more inclusive, but I am speaking of the paths less travelled around here, off those beaten tracks, and for those of us who live within reach of these spaces).

We were commoning when we then each offered up our memories and associations connected to this particular landscape, which most of us live on the urban or peri-rural edges of. These included the remembrance of lost, loved ones through ashes cast into the sea, falling in love on the beach or with particular aspects of nature, discovering family heritage or disclosing secrets here, overcoming fear of water and learning to swim, recalling how ancestors migrated or current family arrived on this coast to start a new life. From this we found more common bonds, intersecting perspectives, and courage.

We were commoning our own belonging, as we walked together as a group of black, brown and women of colour, from the village green of East Dean (heads turning, a couple of terse remarks..) down to Birling Gap beach, in what felt like a joyful act of reclaiming a pathway through the land and speaking/writing with and of it alone and together… and reclaiming for ourselves the ‘emotional possession’ Corinne Fowler refers to at the top of this article in her book Green Unpleasant Land.

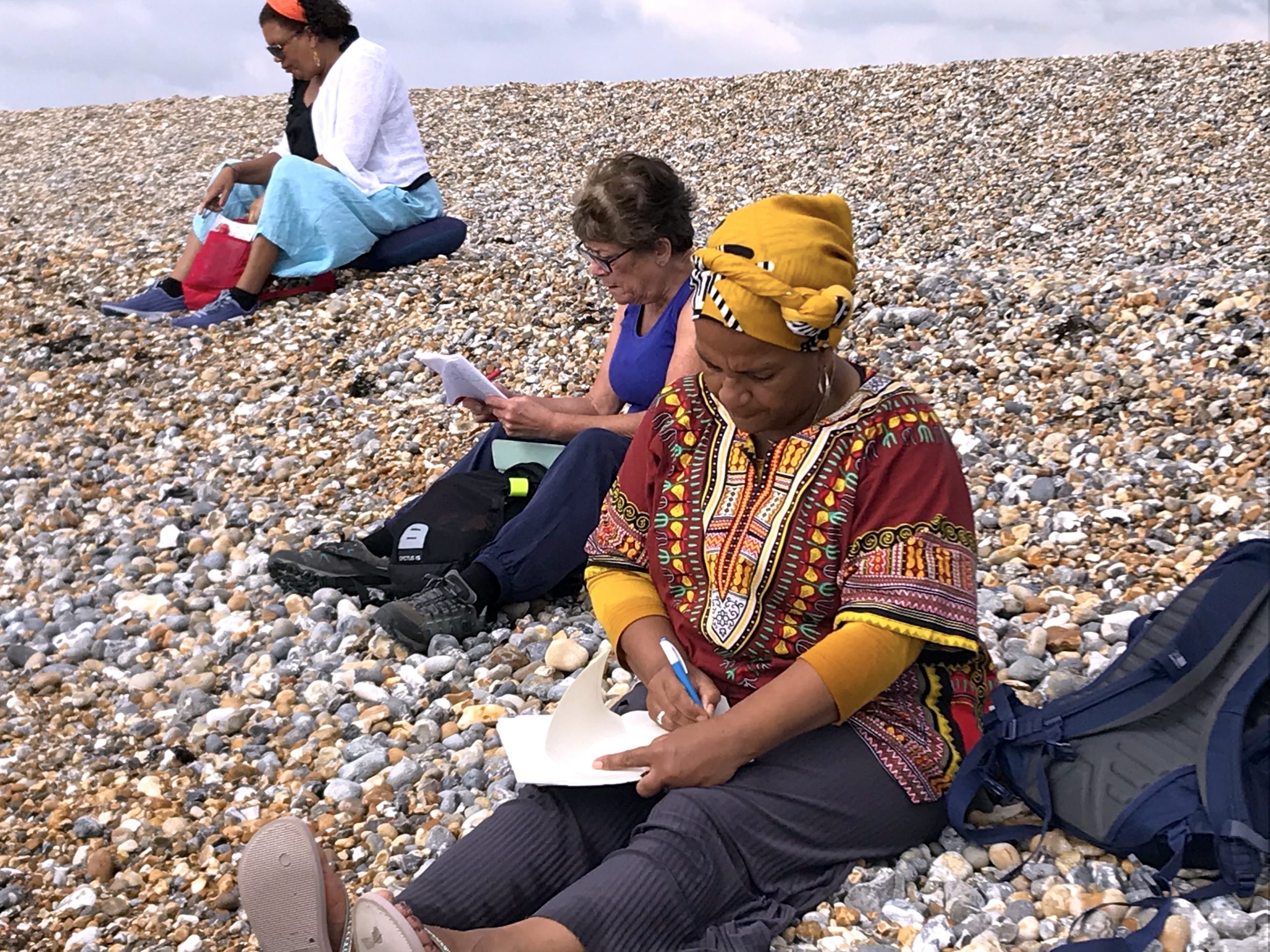

We were commoning when we took our place in on the beach, valley or cliffs, to sit and write and breathe in the open air, find objects there to use as triggers for stories or poetry, and to share these experiences and our work together when we returned to our base, in solidarity with each other and around a table of delicious food.

We were also commoning when we shared with each other the creative tools we each use in our daily lives to inspire us to begin and to keep writing, as well as those we use to stay well, safe, resilient and rested in the face of polarisation, the hostile environment, the climate emergency, and the frenzied culture of productivity that capitalism has had us accelerate our way of being for, for so many years, exhausting many of us, and that this increased connection with ourselves outdoors in nature offer us as a gift to disrupt and question, through the pandemic.

Commoning and kinship

It has got me thinking again about how we can use our words to create new worlds, hopeful ones full of anything we want..(..) I think a lot of the conversations from the retreat have fuelled this feeling more. Also, reflecting on my own connection with nature and with coastal landscapes.. Also, just being with all of our beautiful black and brown group in the landscape – it’s impossible not to feel and recognise the empowerment of our physical presence as a group. And I don’t think I could even have imagined that as a child. So, I want to make sure I’m writing that into stories, writing about that experience, of being a part of this group and reclaiming the land by just being there together.’

Writer participant, We See You Now writing/walking retreat SSCP Sept 2021

This creative and interpersonal commoning between land, the written or spoken word and our human hearts is producing creative kinship and solidarity in the face of precarity, and opening spaces for solidarity and intimacy for those of us at the effect everyday experiences of racism, sexism, ecological anxiety, health issues or mental fragility, exacerbated by pandemic life

The kinship this commoning has produced – fostered by grassroots agencies such as Writing our Legacy who produced the retreats with me, and New Writing South who give so many of us so much support as individual writers moving towards further publication and our writer’s lives and now the support of the Park – is essential to the broader mission of We See You Now and my own residency. The endeavour of decolonising – or, in my more favoured term, of creating equity of voice and visibility within the rural, cultural and natural heritage sector as creative writers and kin of this land – can only work as a collective act, over time, in a spirit of generosity and solidarity. I am grateful that I was working on both these projects in tandem and now see these two parallel aspects of my practice as siblings, with much to teach and learn to/from each other in the months to come.

Alinah’s Seven Sisters /National Park residency podcast The Colour of Chalk is now available across all platforms. Her debut writer/presenter piece on urban/rural nature writing for The Essay – Into the Wild – on Radio 3 will be available from December 17th on BBC iplayer.