25 Nov Breaking borders

Each member of the Crafting the Commons network has been invited to write a post for the blog, capturing their thinking about commons and commoning as the project unfolds. This post is by Jacky Oliver.

Working and teaching throughout the UK, Jacky’s work brings together narratives from a range of sources, contemporary and historic. With a broad and open approach, she creates small handheld objects through to large-scale architectural pieces, for commissions, exhibitions and residencies. Each project is completely unique, interrogating the qualities of a variety of techniques and processes. More information: jackyoliver.co.uk / Instagram / Crafts Council Directory

One of the most exciting parts of my practice is working with others, exploring new ideas and themes. My working process is very fluid, with no preconceived ideas of where the journey might lead. This project has seen more changes in direction than most.

Inspired by the quote from Peter Barnes (On the Commons co-founder) “The commons means: Things we share/ Places we share/ Systems we share/ Ideas we share/ Culture we share” I decided to look at the places, systems and ideas shared in community gardens.

The initial brief for the project mentioned the group Edible Mach Maethlon, a community-led project growing edible crops in Wales. With my keen interest in horticulture and my previous project – Field to Fork for ‘Collect’ – I was interested in looking into the benefits of community gardens, including the physical and mental of gains from working outdoors, the way they bring communities together and the environmental importance, improving the local environment and providing for natural wildlife, all of which I find very inspiring.

Because of lockdown I had to sit at home to research and soon discovered a number of community gardens and growing projects nearby, for once I didn’t need to travel hundreds of miles to gather research.

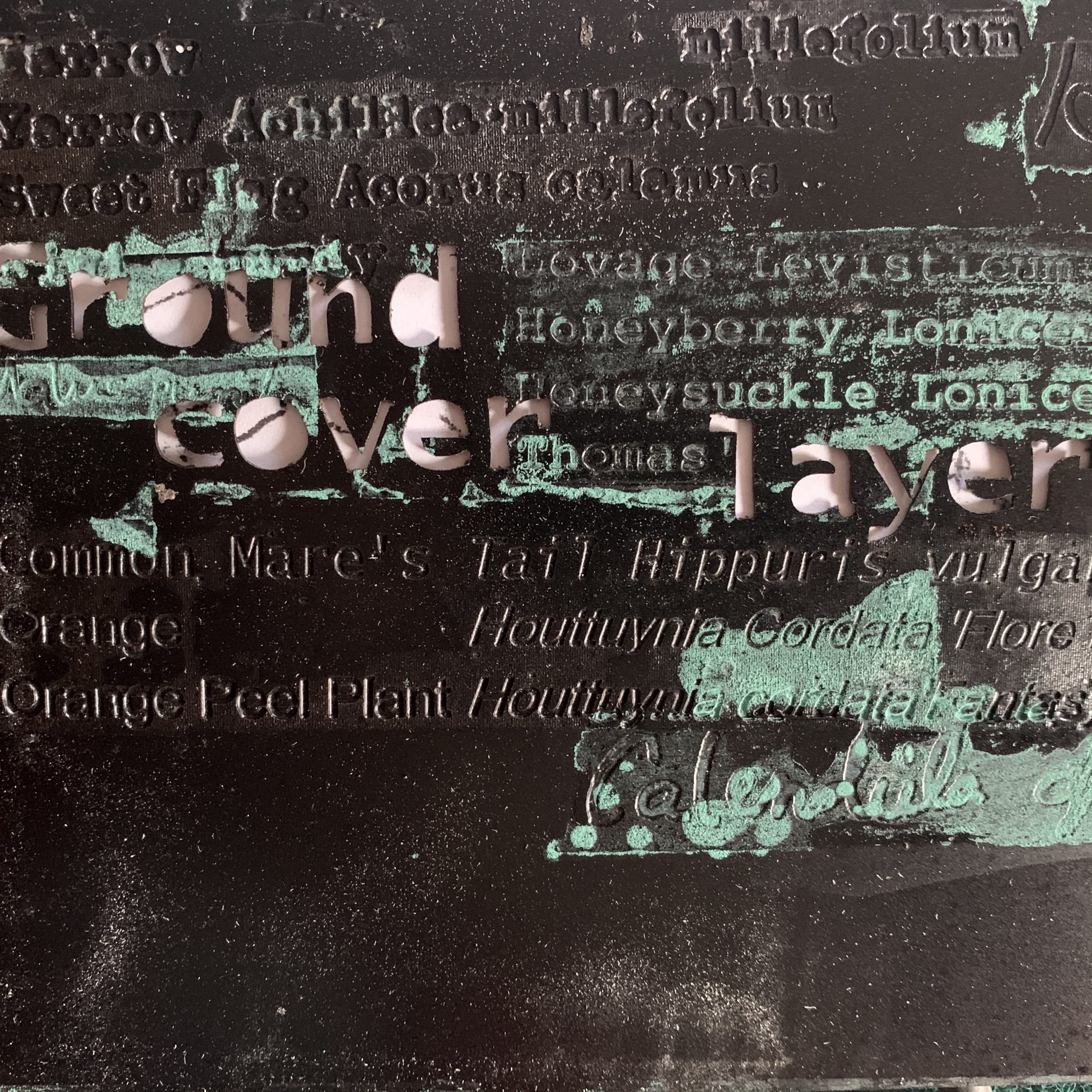

I contacted a number of gardens in London, one of which was ‘Edible Landscapes’. Volunteers learn to grow more of their own food and propagate plants. The project specialises in forest gardening, which mimics natural ecosystems. My first response contrasted the busy built environment surrounding Edible landscapes and actual site, tucked away under a canopy of trees. Here forest gardening cultivates both the plants and the people who tend them.

Volunteers (before Covid) would share a lunch of salad foraged from the garden. I considered ways in which I could bring together both the bowls that hold the foraged lunch and the seven layers of the forest gardening.

Looking at projects that are connecting people with local food, sustainability and engaging skill development led me to the ‘Bees and Refugees’ project set up by Ali Alzein.

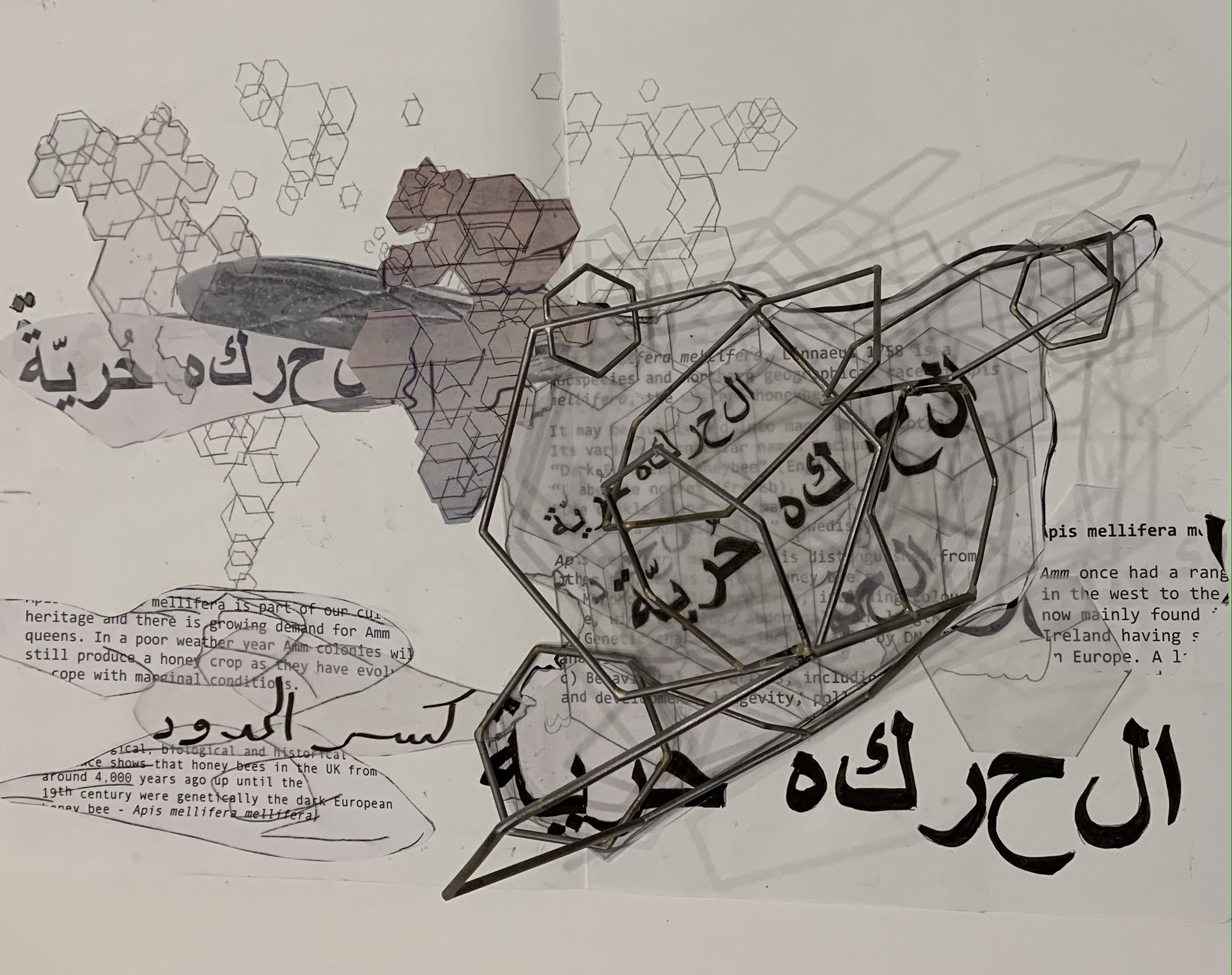

Bees and Refugees “helps with the vitally important task of protecting honeybees and other pollinating insects but helps refugees in our borough who may be struggling to adjust to their new lives.” Ali Alzein, founder of ‘Bees and Refugees’, fled his home and life in Damascus, Syria. Ali talked about the importance of ‘freedom of movement’ and ‘breaking borders’ for many refugees and himself. My initial research had looked back to the history of the ‘Enclosure Act’ and how it displaced people and took away land; I had travelled full circle, on a journey of research, now looking at contemporary narrative.

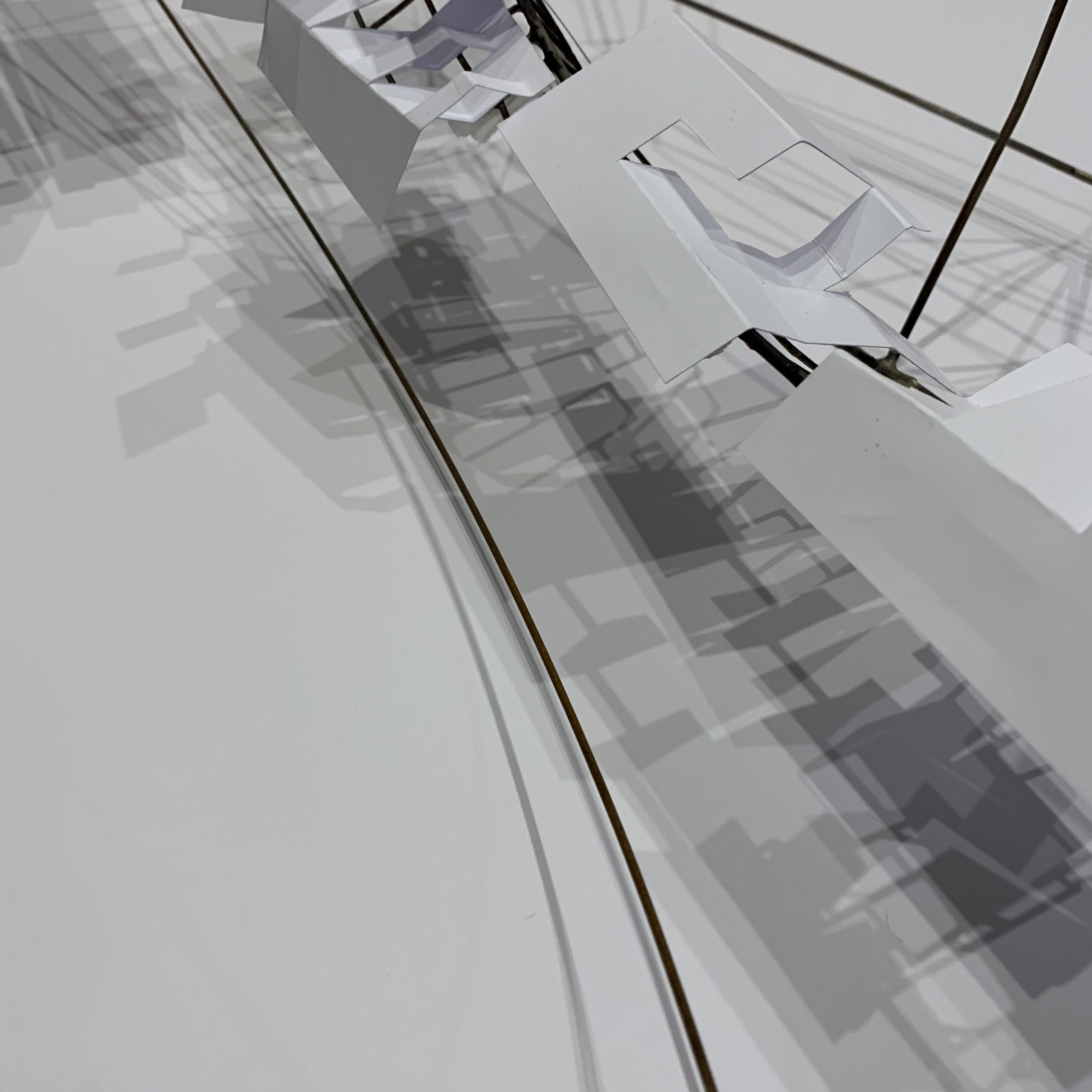

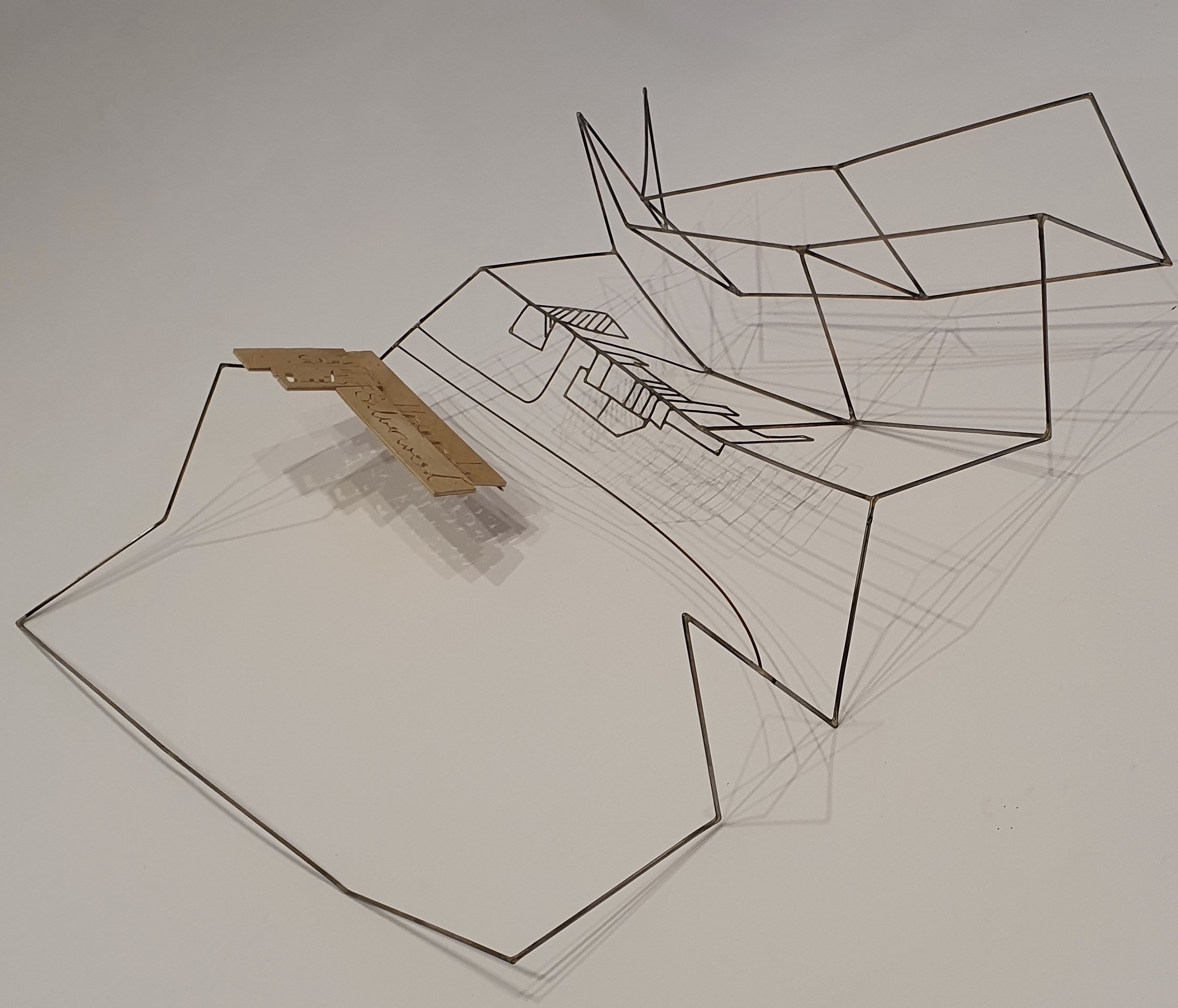

Inspired by the forms of the structure of the honeycombs within the hives, the organized structure has been displaced, recreating the shape of the landmass Syria, but I have deliberately avoided presenting this with a ‘border’. This structure will be refined and then areas will be in filled with etched or enamelled panels with information both about Ali’s journey to the UK, and his experience as a refugee, and the hopes and aspirations of the group. This element of the final outcome will hopefully be added to by other elements developed with information from volunteers from the group.